We asked three participants to inhabit an avatar in Second Life, first without and then with an overlay mimicking a facial burn. We reviewed comments about the virtual world, the impact of the scar, and responses to facial disfigurement questionnaires.

First published by Ether Books, October 2013.

Second Life

We used Second Life (SL), a widely accessible online virtual environment (VE) (Au, 2008), the utility of which has been described elsewhere (Hall, Conboy-Hill, and Taylor 2011). The validity of VEs to model human behaviour is underpinned by extensive research by Bailenson and his team (see Blascovich & Bailenson, 2011). We felt the environment would be suitable for this study because it would balance field versus laboratory (control v realism) issues, and eliminate the need to recruit people with facial disfigurement (FD) or ask participants to wear a prosthetic.

Presence

‘Presence’ is an important VE concept reflecting a user’s sense of being in a VE. The Proteus Effect (Yee & Bailenson, 2007) is a phenomenon whereby changes to a user’s avatar impacts on both in-world and real life behaviours. This impact is described as transformational and underpins much of the theoretical and empirical structures informing VE research. For VEs to be effective as a clinical or research tools, ‘presence’ and transformational capability seem essential.

Disfigurement

The experience of disfigurement is generally negative, and so people tend to avoid social situations (Kent 2000). Hence, there is likely to be a demand for interventions and support online for socially or geographically isolated people but FaceIT, (Bessell, Clarke, Harcourt, Moss & Rumsey, 2010) is the only one currently available.

Virtual reality is increasingly being used for a variety of other psychological difficulties (Parsons & Mitchell 2002; Parsons, Leonard & Mitchell 2006; Price and Anderson 2006; Inan 2008). This study is a small scale exploration of the feasibility of a VE for FD research and support.

Design

In a case study design, we asked three people without FD to use SL with a facial burn attached to their avatar. We explored a priori themes via semi-structured interviews based on existing research on VE immersion and disfigurement. These were:

- Identification with the avatar and SL ‘presence’ prior to the FD being attached.

- Participants’ reactions to the change to their avatar’s face

- Social interactions in SL before and after the FD is attached.

Method

Participants

The three participants (2 male: P1 & P3; 1 female: P2) were aged 22-23, and had no visible disfigurement in real life. Two were Sussex University students, whilst the third was in full time employment. They were paid £15 on completion of two separate one hour sessions.

Materials

The latest version of Second Life Viewer was installed on a desktop computer that had a broadband internet connection and an ATI Radeon HD 4800 graphics card installed. There was an on-screen inventory that permitted a guided exploration of options available to participants in SL. The sessions where the FD was attached began in a VE area that was sparsely populated.

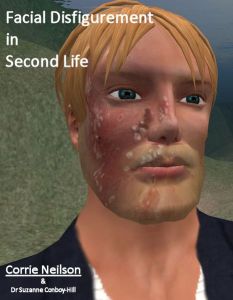

We used a generic, customisable avatar that could appear as either gender, and dressed it in the wardrobe described by SL as ‘student’. It was labelled ‘RD1’.

The FD was a bitmap representing a radiation burn which earlier feedback had suggested was realistic. It could be applied easily by the researcher (Corrie Neilson – CN) by clicking on it in the avatar’s inventory.

Interviews were recorded on a digital voice recorder, and notes made as a contemporaneous record of people’s responses. After the second session, we asked participants to complete a Body Image Coping Strategies Inventory (BICSI – Cash 2005) which measures cognitive and behavioural coping strategies adopted by people to deal with body image challenges.

Measures

These were the 29 items of the BICSI. They identify three main coping styles: appearance fixing, positive personal acceptance, and avoidance. We adapted the wording to reflect the hypothetical nature of the questions so that “what do you do?” became “what would you do?”.

Procedure

The sessions were designed to facilitate open discussion in a semi-structured context. Prior to each first session, we modified the gender of the avatar to mirror that of the participant, although they could change this if they wished.

Session One

The main focus of this session was familiarisation with SL. Participants could explore the VE with guidance (CN), e.g. editing the look of their avatar and navigating the interface. During this session, participants were asked about their impressions of SL through an ongoing semi-structured interview.

Session Two

Where possible, we edited each avatar to look as it had at the end of each participant’s first session. If the interval between sessions exceeded two days, we gave people a little time to re-acquaint themselves with SL.

Once re-familiarised, participants left the room while we attached the FD. They had not been aware that a disfiguring scar would be attached and so now saw it for the first time. We said they could remove the burn if they wished, and explored participants’ reactions to the disfigurement over the remaining hour. They completed the BICSI at the end of the session and left after debriefing.

Results

The interviews were transcribed verbatim, and analysed by two separate researchers, using Pope, Ziebland & Mays (2000) method of Framework Analysis. Focus was on the content in accordance with the previously identified a priori themes.

Identification with the avatar and ‘presence’

The experience of the virtual environment differed for each participant. P1 and P3’s perceptions of their real life identity influenced their avatar editing choices. P1 wanted to create an avatar that mirrored his real life look, spending twenty minutes choosing an outfit that he “might realistically wear”, and adjusting the hair to mirror his own. He joked about how “picky” he was being, but continued to adjust the appearance before he was happy to use SL for anything else. He then gave his own name to the modified avatar, and addressed it by that name throughout session one. When asked about his choices, P1 said that he would feel more “comfortable and honest” with an avatar that looked like him. Following this, P1’s immersion within the virtual environment was apparent when RD1 was left momentarily naked in front of others. He responded with embarrassment and announced “This has new player written all over it”.

In contrast, P3 removed all traces of an appearance that might reflect his own – “I hate things that look like me”. He concluded that the modified avatar was “who I wanna be”. P3 edited the face by attaching a beard but kept the everything else as before. On observation, the modified avatar seemed to look like P3, plus the beard.

P2 spent least time modifying the avatar. She kept the shape and facial features, but changed the outfit. Her first comment was that “she doesn’t look like a student”, referring to the outfit provided by SL. She then spent time changing the clothes to ones she said she “wouldn’t wear in real life” but she felt “alright” about. She made frequent remarks about how “fake” the VE felt.

Social Interactions and other avatars

Participants responded differently to SL’s social opportunities. P1 was relatively at ease, engaging in local and private chat with other avatars. He was confident in his ability to be socially attractive to other residents, and commented about getting “a second life girlfriend”.

P2 and P3 were less confident and approached social interactions by reading ongoing public chats amongst the other SL residents, P2 commenting that “they say stupid things”. She questioned whether people form friendships in-world and talk about “controversial issues…like politics”. She observed others but did not initiate any conversations.

P3 did initiate conversations, but spent time choosing the most appropriate avatar with whom to engage, basing suitability on screen name and overall appearance. P3 seemed anxious in-world and uncertain in his real life behaviours. He said that if there was no response from people he approached in-world, he would feel “rejected”. He demonstrated this by walking his avatar into the sea when he “couldn’t handle” an ongoing conversation.

All three participants wanted to authenticate the identity of the other SL residents, and both P1 and P3 commented on their assumptions about the real life identity of “sexy” (P1) or “scantily clad” (P3) female avatars. They were both adamant that these avatars were likely owned, in real life, by a “bloke” (P1) or “some weird guy” (P3). They also both said that those avatars who appeared “normal” (P1) were more likely to reflect the look of the corresponding user. P2 reserved judgement and reflected instead on whether other avatars were controlled by “real people”.

Reaction to the FD

All three participants agreed to use SL with the FD attached to their avatar. Both P1 and P3 said that, knowing they could remove it lessened any social anxieties they might have felt. P1 commented that he was “using [RD1] for the sake of an experiment” and would not “choose” to put the burn on his own avatar. P3 similarly commented that “these characters can be changed and that’s the key point for me”. P2 on the other hand, showed little response to the scar because “it’s not me”, and so a facial scar in SL “wouldn’t really matter”. This reflected her behaviours in session one, in which she spent least time modifying the avatar, and said she felt the environment was “fake”.

All three participants now identified less with the avatar they were using. Both P1 and P3 distanced themselves from any previous ownership; P1 referred to the avatar as “RD1”, rather than his own name and also said that “…yesterday I saw him as being this kind of smart cool guy, whereas now I feel sorry for him”. Similarly, in response to seeing the scar again, P3 laughed saying “I’ll admit I kind of want to take it off”. However, none of the participants did actually ask to remove the scar.

The participants’ social behaviours in-world with the FD did not differ from their first session. P1 continued to engage in the social element of SL to “see how my new face reacts”. His behaviours though, seemed confrontational and an attempt to get a reaction from other residents – “I just want someone to proactively ask me about it” – and he was disappointed when this did not occur. As a result, he asked people whether they noticed anything “wrong” with his appearance. He received friendly comments that the look was original. Both P2 and P3 avoided social interactions for the same reasons as before, saying they had nothing to talk about.

Results of the BICSI

The three participants identified different real life coping behaviours they felt they would adopt. P1 predicted he would follow a positive rational acceptance style (mean score 1.81) if living with disfigurement. Whereas P2 speculated that she would adopt an appearance fixing approach (mean score 1.9) and P3 would adopt more avoidant coping behaviours (mean score 2.13). These were not consistent with the behaviours they adopted in-world when using the disfigured avatar, as no participant removed the scar or tried to fix the avatar’s appearance once the scar was attached.

Discussion

‘Presence’ without FD

Evidence of virtual presence prior to attaching the facial scar was apparent in the social and appearance adjusting behaviours of the participants. All modified RD1 early in the initial session to illustrate their personal preferences. For one, this included claiming ownership by giving the avatar his own name.

At times, each participant showed emotional investment in the social content of the virtual environment. Specifically, feelings of rejection, embarrassment or social anxiety were reported by all, which resulted in one participant avoiding any virtual conversations. P2, whilst ostensibly maintaining a social distance, was nevertheless concerned about what her avatar ‘felt’ or ‘wanted’.

‘Presence’ with FD

Following the attachment of the FD, two participants re-defined their virtual identity and used the on-screen name for the avatar. This distancing seemed to highlight their changed perceptions, and led one participant to adopt a more confrontational stance towards other SL residents.

The behaviour of one participant in particular seemed avoidant following the attachment of the FD. He referred to the avatar as RD1, whereas previously he had given it his own name. Two participants expressed sympathy for the avatar, where they had previously felt a sense of personal affinity. This reflects earlier research detailing avoidant coping behaviours of people with visible disfigurement (Kent 2000).

Transformational potential

We found differences among the coping styles identified by participants’ responses on the BICSI and their behaviours in-world. One participant’s scores favoured appearance fixing behaviours, and yet these behaviours were not demonstrated in-world. The two participants who said they would not attach such a feature out of choice, did not identify appearance fixing as their preferred coping. The discrepancies between the BICSI scores and behaviours in-world suggest future research directions evaluating the longstanding problem of divergent expressed and reported attitudes (e.g. Gahagan, 1980).

Conclusion

We explored the use of SL for FD research, looking for evidence of ‘presence’ in the VE to support validity of experience. We believe this was demonstrated sufficiently to justify further focus on VEs for clinical research. There was also indication of inconsistency between attitudes expressed and corresponding behaviours, which promises better clinical evaluation of this confounding factor in effecting change.

References

Au, W. J. (2008). Notes from the new world: The making of second life. New York, NY: Harper Collins Publishers, pp IX – X and 252.

Bessell, A., Clarke, A., Harcourt, D., Moss, T. P. & Rumsey, N. (2010). Incorporating user perspectives in the design of an online intervention tool for people with visible differences: Face IT. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 38, 577-596.

Blascovich, J. & Bailenson, J .(2011). Avatars, eternal life, new worlds and the dawn of the virtual revolution: Infinite reality. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, pp 102- 115.

Cash, T. F. (2005). Manual for the body image coping strategies inventory, purchased from http://www.body-images.com/assessments/bicsi.html (29/10/2010 at 16.17).

Gahagan, D. (1980). Attitudes. In: Radford, J. and Govier, E. A Textbook of Psychology, Ch 27. Sheldon Press.

Hall, V., Conboy-Hill, S. & Taylor, D (2011). Using virtual reality to provide health care information to people with learning disabilities: acceptability, usability, & potential utility The Journal of Medical Internet Research, 13 (4) e109. http://www.jmir.org/2011/4/e91/

Inan, F. (2008). Virtual reality and social phobia: Recreating a social situation in virtual reality. Unpublished Masters, Delft University of Technology.

Kent, G. (2000). Understanding experiences of people with disfigurement: An integration of four models of social and psychological functioning. Psychology, Health and Medicine, 5, 117-129.

Parsons, S. & Mitchell, P. (2002). The potential of virtual reality in social skills training for people with autistic spectrum disorders. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 46, 430-443.

Parsons, S., Leonard, A. & Mitchell, P. (2006). Virtual environments for social skills training: Comments from two adolescents with autistic spectrum disorder. Computers & Education, 47, 186-206.

Pope, C., Ziebland, S. & Mays, N. (2000). Qualitative research in healthcare: Analysing qualitative data. British Medical Journal, 320, 114-116.

Price, M. & Anderson, P. (2006). The role of presence in virtual reality exposure therapy. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21, 742-751.

Yee, N. & Bailenson, J. (2007). The Proteus effect: The effect of transformed self-representation on behaviour. Human Communication Research, 33, 271-290.

2499 words

Acknowledgments

This work was completed as part of the first author’s MSc in Foundations of Clinical Psychology and Mental Health with the university of Sussex. We would like to thank Dr Kate Cavanagh for her support throughout.

Affiliations

Corrie Neilson: 33 Handsworth Avenue, London. Email: corrie.neilson@gmail.com

Suzanne Conboy-Hill: Consultant Psychologist, Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust, & Visiting Clinical Research Fellow, University of Brighton.